Aspen History

The History of Aspen is the Story of a Town of Changing Economies

Archaeologists recently discovered that ancient people made their homes in the mountains near Aspen, Colorado 8,000 years ago. Ute Indian tradition says that these “Shining Mountains'” have always been their homeland. First silver and later near-perfect snow conditions enticed more recent settlers to the Roaring Fork Valley. Leadville was the second largest city in Colorado in 1879, when Leadville prospectors crossed the Continental Divide into the Ute’s summer hunting territory to discover one of the richest silver lodes the world has ever known. They named their camp Ute City, but by spring the name had been changed to Aspen. Many mining camps were temporary settlements. Aspen had the winning combination of rich silver ores, two competing railroads, and ample investment from wealthy Victorian capitalists such as Jerome B. Wheeler, President of Macy’s Department Store and Cincinnati lawyer and businessman David Hyman.

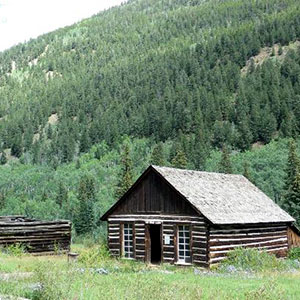

Aspen quickly became an urban, industrialized community with impressive architecture, leaving Independence, Ashcroft, and Ruby to become ghost towns. By 1890 the production of Aspen’s silver fields had surpassed even rival Leadville, making it the nation’s largest single producer. By 1893 Aspen’s 12,000 residents had six newspapers, four schools, three banks, electric lights, a modern hospital, two theaters, an opera house, and a very small brothel district. Aspen’s fortunes fell with the U.S. government’s return to the gold standard in 1893. Ironically, one of the largest nuggets of native silver ever found was mined in 1894 in Aspen, weighing in at almost 2,200 pounds. With minimal commercial silver markets, Aspen survived as a rural county seat and ranching center as mining declined.

Just 700 people called Aspen home in 1935, when international outdoorsmen came to the Roaring Fork Valley in search of the ideal location for a ski resort. They hired the famous Swiss avalanche expert Andre Roch to develop a ski area based in the ghost town of Ashcroft, but had to cancel their plans with the outbreak of World War II. Meanwhile, Andre Roch and the enthusiastic Aspen Ski Club cut a race course on Aspen Mountain, served by a “boat tow”-two massive sleds pulled up the hill by an old mine hoist and a gas motor.

While plans for a ski resort were delayed by the War, later ski development was actually enhanced by the presence of the Army’s 10th Mountain Division, training in nearby Camp Hale. Many soldiers skied in Aspen while on leave, and some, including Austrian Friedl Pfeifer, planned to return in peacetime. Pfeifer teamed up with Chicago industrialist Walter Paepcke and his art patron wife Elizabeth. The Paepckes were interested in the community’s potential as a summertime cultural center; Pfeifer hoped to build a ski resort on a par with Europe’s best. In 1947 Aspen Mountain opened with the world’s longest ski lift. In 1949, Paepcke, with the University of Chicago, masterminded the Goethe Bicentennial Convocation in Aspen, celebrating the great humanist’s 200th birthday with international leaders, artists, and musicians. The music, art, dance, theater, and international studies programs that developed assured Aspen’s role as a cultural center. The very next year, Aspen became the first ski resort in America to host an international competition, precursor of today’s World Cup races.

Three more mountains — Buttermilk (1958), Aspen Highlands (1958), and Snowmass (1968)- added to Aspen’s reputation as a premiere international resort and Aspen flourished in summertime with the combination of climate, recreation, history, and culture. The unanticipated growth of an appealing community based on world-class skiing and culture spurred a divided local population to turn to zoning and later to adopt growth control measures. From hunting territory to mining city, through the “Quiet Years” as an agricultural center to the present, the history of Aspen is the story of a town of changing economies with a distinct mix of locals and outsiders, recreation and culture, landscape and sport.

A substancial Community

Log Buildings Came Quickly

Impressive Architecture